Today’s article is all about plumbing vents…

Let’s start by testing your knowledge…

Can you correctly answer this one question plumbing quiz?

What’s the “primary” purpose of a plumbing vent?

A. Better Drain Flow

B. Protect trap seals

C. Transport sewer gas outside

D. To vent the sewer

Here’s a hint…the answer is not “A.”

According to the ASPE (American Society of Plumbing Engineers), better drain flow is just a “secondary effect” of plumbing vents.

Few people understand a plumbing vent’s true purpose.

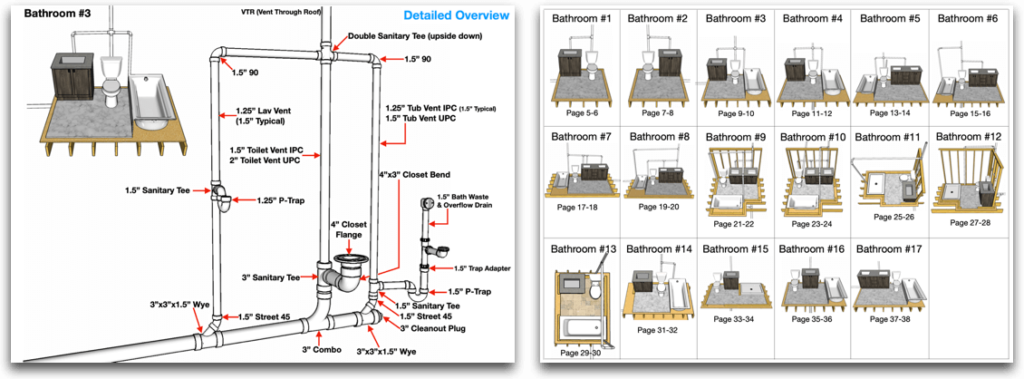

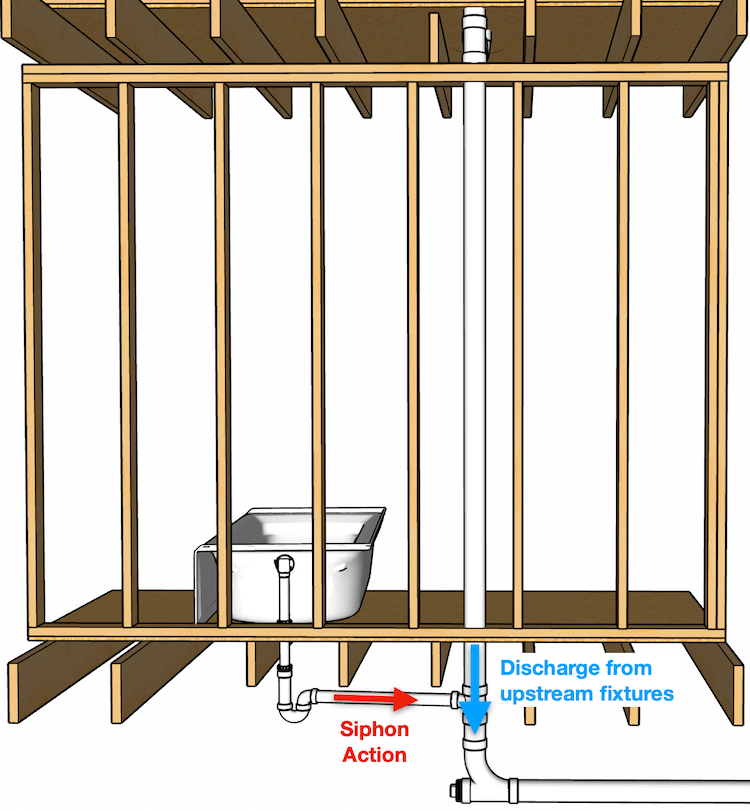

To help answer this important question, look at the plumbing vent diagram below:

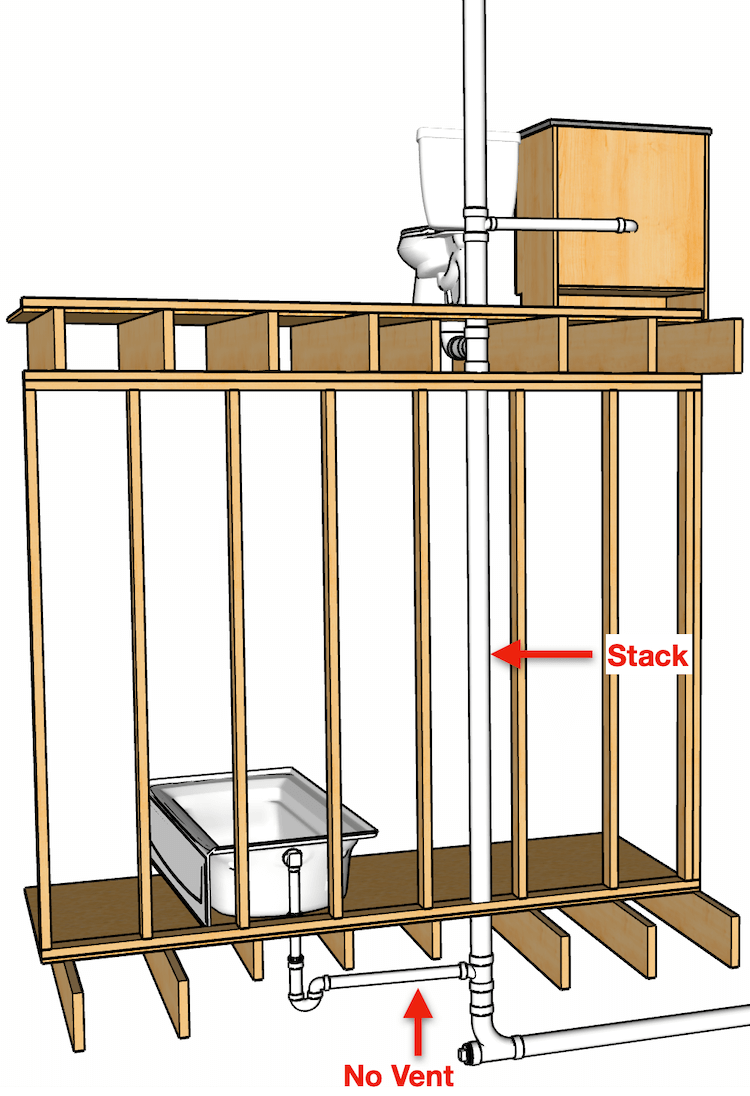

Notice the floor 1 bathtub has no vent.

As waste flows down a stack, it draws air with it.

The moving air also draws nearby fluids…

This is called the boundary layer effect.

When the waste (blue arrow below) flows past the unvented tub drain, pressure fluctuations (red arrow) are created.

In this example, negative pressure is created.

Changes in pressure like this can be detrimental to trap seals.

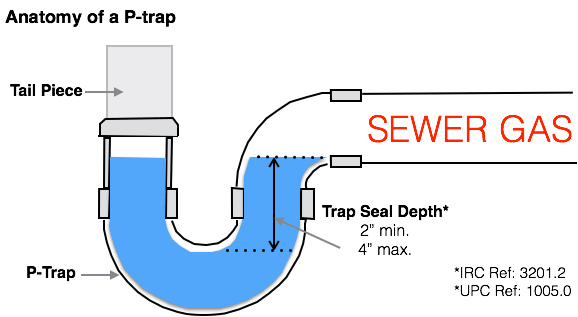

What’s a trap seal?

The trap seal is the standing water inside a P-Trap…

This crucial water seal blocks unwanted sewer gas from entering your home.

When pressure fluctuations inside the drainage system are severe enough, the seal gets siphoned right down the drain.

The consequence?

The p-trap becomes a useless piece of empty plastic and sewer gas enters the home.

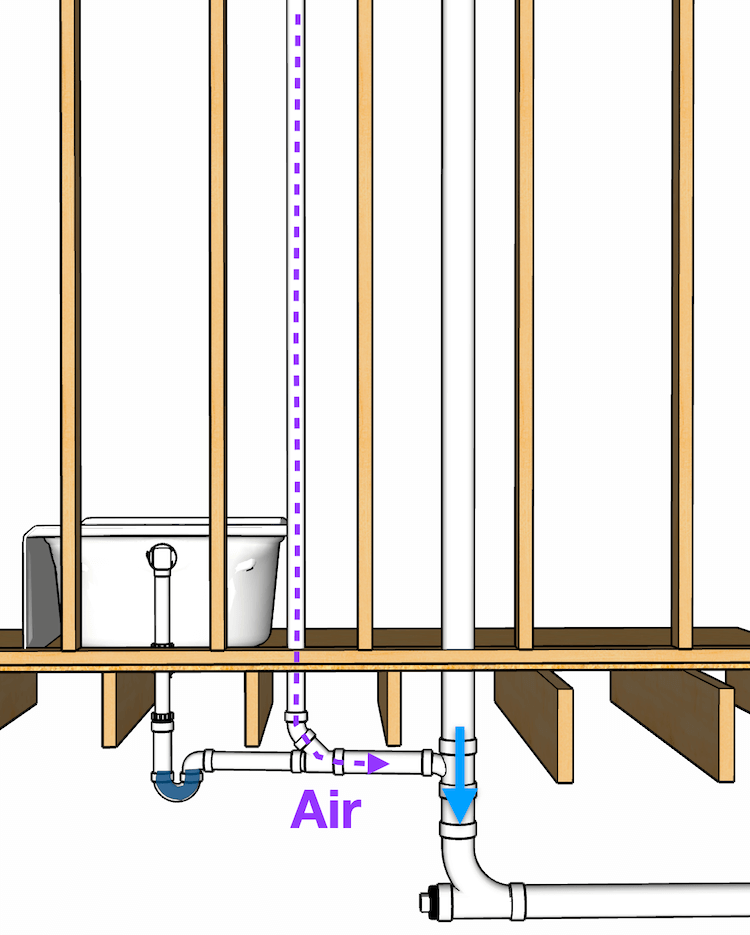

However, a properly installed plumbing vent changes everything.

How? The vent introduces air into the drainage system.

The introduction of air breaks the siphon…

And the precious seal stays in the trap.

Upstream fixtures can now flow past the tub’s drain…

Why? Because the tub’s trap is protected (thanks to the vent).

This is how traps and vents work together to keep your home safe.

Remember this…

The primary purpose of a plumbing vent is to protect trap seals.

How do plumbing vents protect trap seals?

By balancing the air pressure inside the drainage system.

The 2 atmospheric forces vents protect against are:

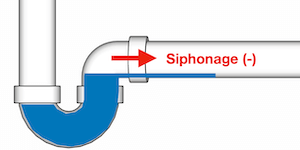

- Siphonage (negative pressure)

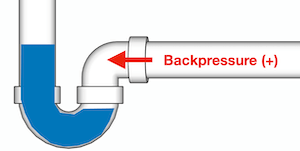

- Backpressure (positive pressure)

Siphonage (or negative pressure) occurs when the atmospheric pressure on the discharge side of the trap is lower the inlet side. The trap seal goes down the drain as a result (like the bathtub example above).

Backpressure (or positive pressure) occurs when the pressure on the discharge side of the trap is greater than the inlet. The trap seal is forced towards the fixture.

Both forces are enemy of the trap seal…

That’s why it’s crucial each plumbing fixture is properly vented…

Otherwise, you saw the consequence (in the above plumbing vent diagram) of not installing a plumbing vent.

It’s also worth mentioning the secondary benefits of plumbing vents…

Or as the ASPE says, “secondary effects” of venting.

The secondary benefits of a plumbing vent include:

- Better drain flow

- Lower drain noise

- Sewer gas is transported outside

- Public sewer is vented

- Primary chamber of a septic tank is vented

But remember, the main reason plumbing vents are installed is to protect trap seals…

Chapter 9 of The IPC Code and Commentary sums up venting nicely,

“If there were no traps in a drainage system, venting would not be required. The system would function adequately because it would be open to the atmosphere at the fixture connections thereby allowing airflow.”

By the way…

Here’s something you’ll find helpful…

I’ve put together step-by-step diagrams showing exactly how to piece together complete bathroom drain and vent systems.

- Work perfectly with both IPC & UPC codes (so you’ll NEVER fail inspection)

- Show you EXACTLY what goes where (zero guesswork)

- Use plain English (not “plumber speak”)

The best part?

Almost 1,000 DIYers have already used it to plumb their dream bathroom.

You can too.

Grab Your Copy of The Plumbing Library Here >>

Moving along…

Now that you understand the purpose of a plumbing vent, let’s discuss how plumbing vents are installed…

According to the plumbing code, every P-Trap needs vented via an approved “venting method.”

901.2.1 of the IPC says it like this, “Traps and trapped fixtures should be vented in accordance with one of the venting methods described in this chapter.”

The different venting methods:

- Conventional Venting (Individual Venting)

- Common Venting

- Wet Venting

- Circuit Venting

- Combination Waste and Vent

- Island Fixture Venting (aka Island Sink Vent)

- Waste Stack Venting

- Single-Stack Venting

Important note: The United States doesn’t have a unified plumbing code. The two main codes are the IPC (International Plumbing Code) and the UPC (Uniform Plumbing Code). These codes have many things in common. However, great differences also exist between these two codes. A venting method permitted in one jurisdiction, may (or may not) be permitted in another jurisdiction. For example, AAVs (Air Admittance Valves) are allowed in IPC jurisdictions. However, the UPC does not allow AAVs to be installed, unless the local code (Authority Having Jurisdiction) approves.

With that being said, the simplest and most commonly used venting method is called:

Conventional Venting.

This venting method is approved in all plumbing codes (assuming installed correctly).

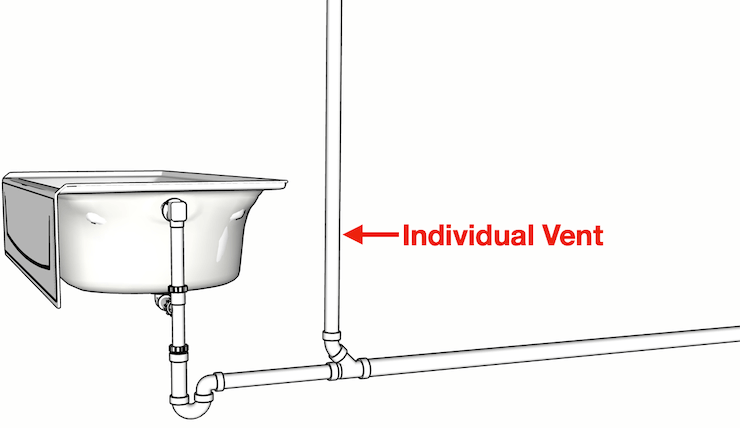

Conventional Venting is when each fixture has its own plumbing vent.

This plumbing vent is called an…

Individual Vent

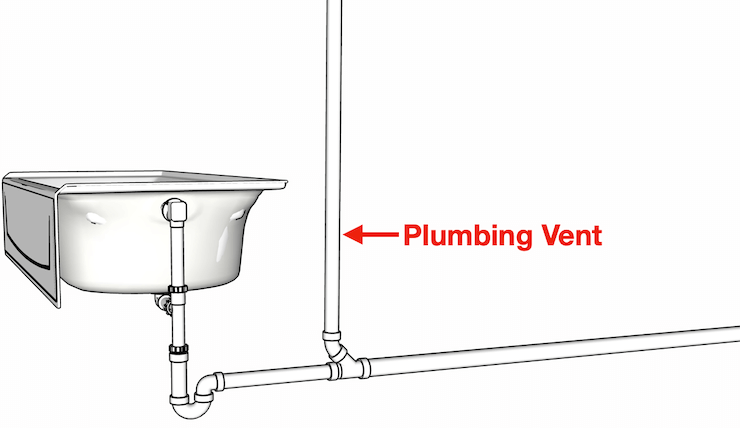

An individual vent is a single pipe that vents a plumbing fixture’s trap.

The bathtub’s vent in the example above is an individual vent and here’s a great example of a bathroom plumbed conventionally.

This vent pipe can terminate outdoors to open air (through the roof) all by itself.

Or some codes, like the IPC, allow an individual vent to terminate to an…

AAV (Air Admittance Valve).

An AAV is a one-way valve that allows air to enter the drainage system when negative pressure exists. Once the pressure returns to normal, the AAV closes by gravity and seals off the vent.

A properly installed AAV is an easy way to vent a plumbing fixture, however, some codes don’t allow them. Check with your local building department before installing an AAV.

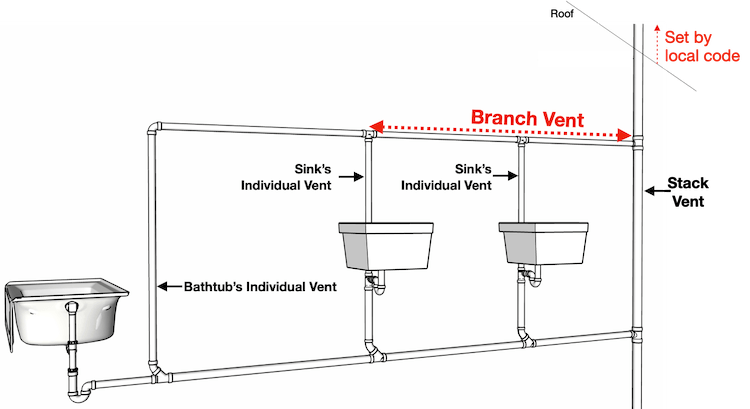

Many times, individual vents connect to other individual vents…

This creates a…

Branch Vent

A branch vent is a vent pipe that connects one or more individual vents to either a vent stack or stack vent.

The vent stack or stack vent eventually terminates outdoors to open air through the roof.

The height above the roof the plumbing vent terminates is set by your local plumbing code.

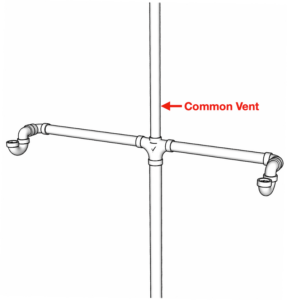

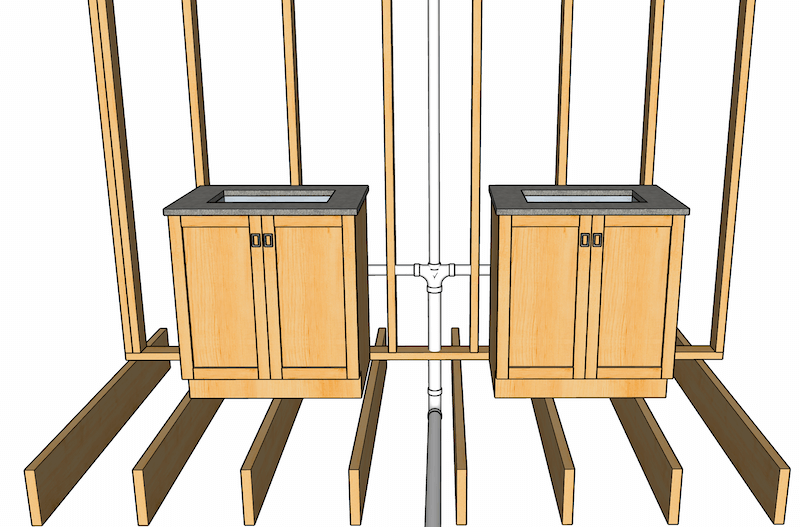

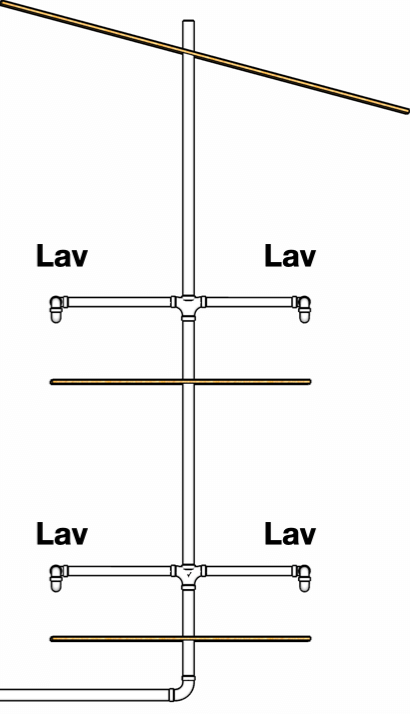

Common Vent

A common vent is an individual vent that connects at the intersection of two trap arms.

This is a convenient way to vent two plumbing fixtures with one vent pipe.

Typically the fixtures are set “side-by-side” or “back-to-back.”

For example, a double bath lav or back-to-back bath lavs.

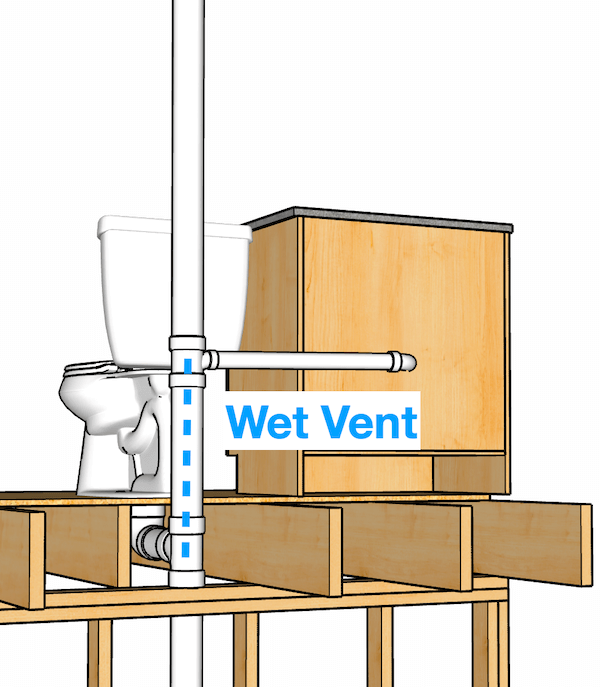

Wet Vent

A Wet Vent is a pipe that serves as both a drain and a vent…

That’s the most basic definition.

Wet venting is a great way to plumb a bathroom with one vent.

It’s also a popular choice among pros because it’s fast, efficient and requires less fittings than a conventionally plumbed bathroom.

Both major plumbing codes allow wet venting. However, each code has special sizing requirements because the pipe acts as both a drain and a vent.

To see examples of bathrooms plumbed with wet vents (along with the proper sizes)…

Check out Bathroom # 13, 14, 15, 16 and 17 in our ebook of bathroom plumbing diagrams.

Get all the details on this page >>

The two main types of wet vents include:

- Horizontal Wet Vents

- Vertical Wet Vents

The plans above include both types.

Keep in mind, wet venting is limed to fixtures belonging to one bathroom group in the UPC.

Or in the IPC, one properly installed wet vent can vent two bathroom groups. This assumes both bathrooms are on the same floor.

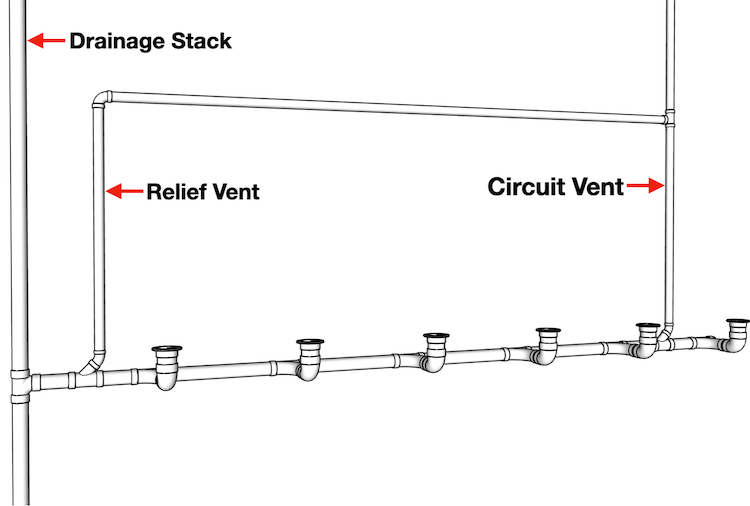

Circuit Venting:

A circuit vent is an efficient method of venting a battery of plumbing fixtures with one single vent. Both the IPC and UPC permit circuit venting (Chapter 9). The circuit vent connects between the two most upstream fixtures. As few as 2 fixtures or a maximum of 8 fixtures may be served by the circuit vent. The circuit vent diagram below shows both the circuit vent and a relief vent.

Plumbing codes also require the installation of a relief vent when the following conditions occur:

1.) Four or more water closets connect to the circuit-vented horizontal branch drain; and

2.) The circuit-vented branch drain connects to a drainage stack receiving discharge from fixtures on an above floor (see the above plumbing-vent-diagram and check local code).

Interestingly enough, circuit venting has been around since the 1920’s. Dr. Roy Hunter even included circuit venting in the Building Materials and Structures Plumbing Report BMS66 Plumbing Manual published in 1940.

Combination Waste and Vent System (CWV):

A special venting method using the horizontal wet venting of one or more sinks, floor drains, lavatories or drinking fountains by means of a common waste and vent pipe.

This pipe is oversized to allow the free movement of air (above the drain’s flow line). Due to the oversized pipe, a CWV system loses its self-scouring (self-cleaning) characteristics. To prevent drain blockages, plumbing codes restrict what fixtures can use this system…fixtures producing “waste” only are permitted. Toilets, urinals, and clinical sinks are not allowed.

The IPC and UPC have drastically different requirements for combination waste and vent systems. See section 915 for those in the IPC. Or in the UPC, checkout section 910 along with Appendix B for detailed notes.

The 2018 version of the IPC does not allow sinks with food waste disposers, however, the 2021 version of the IPC does allows food waste disposers. This recent change gives installers (in the right jurisdiction) an easy option to vent island sinks.

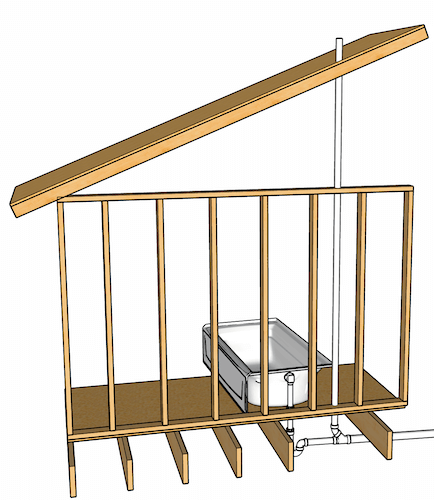

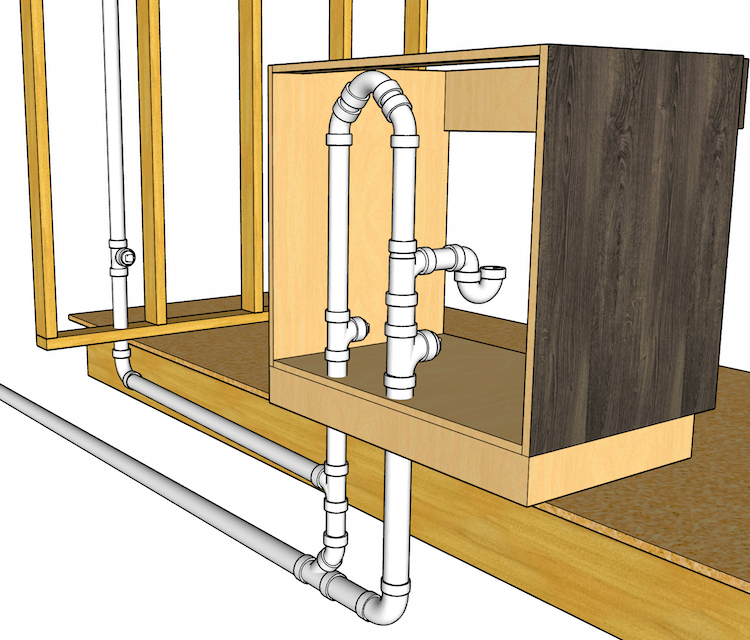

Island Sink Vent

This vent has many names: loop vent, island vent, island sink vent, bow vent and Chicago loop vent. The IPC refers to this method of venting as Island Fixture Venting.

When an individual vent cannot be installed because a sink isn’t next to a wall, an island sink vent is a possible solution. This vent differs from a conventional individual vent because it offsets horizontally below the sink’s flood level rim.

Both codes allow island vents but keep in mind this venting method is limited to specific fixtures located “in an island.”

In the IPC, those fixtures include sinks, lavatories, and residential kitchen sinks. The sink is also allowed to have a garbage disposal and/or a dishwasher (see 916.1).

The UPC limits island venting to traps for island sinks and “similar equipment.” See section 909 for more information.

Waste Stack Venting

A waste stack vent is a special venting method covered under section 913 of the IPC.

Please note: The UPC does not permit waste stack venting.

The general idea behind waste stack venting is fixtures (other than toilets and urinals) use the oversized waste stack as the vent.

This system is limited to “waste” only. Toilets and urinals are not permitted to discharge into the waste stack.

Additionally, a special table in the code is used to oversize the stack.

Vertical and horizontal offsets are not allowed and a full size stack vent is also required.

This system has also been called multistory stack-venting, Philadelphia single-stack and multi-story vertical wet vent. But again, the IPC refers to this venting method as a Waste Stack Vent.

Single-Stack Venting:

This venting method is similar to waste stack venting combined with the combination waste and vent (CWV) method. This system relies on an oversized drainage stack and oversized branch connections to serve as both the drain and the vent.

This venting method was added to the IPC in 2012, however, it hasn’t gained mass popularity as there are many special rules and limitations. See section 917 in the IPC for more information.

In the UPC, single-stack vents are rare. Appendix C in the UPC requires an engineered design by a registered design professional before installing a single-stack vent.

That sums up this article on plumbing vents…

If you’d like to learn more about venting and plumbing in general we have some free training below…